The Optical Printer

The Canyon Cinema Optical Printer Story – Loren Sears

To correct some misunderstandings: I invented the table-top optical printer and wrote an article on how to build it for the July 67 Canyon CinemaNews. There was a mistake by Edith Kramer in Scott MacDonald’s interview on page 77 of the Radical Light anthology, where she incorrectly attributed its invention to fellow Canyon filmmaker, Lenny Lipton, instead of Loren Sears. The impersonal tone of my article was inspired by the Diggers’ habit of adopting anonymous collective identity. (see below)

I developed the optical printer in order to make a freeze frame for one my first films (Merry Go Round, that’s not in circulation.) I naively intended to just duplicate 5 seconds of the last frame of the film and splice it back onto the end. This was summer 1966.

I asked John, a tech. at Leo Diner Film Lab in San Francisco, how to make a freeze frame. He told me the optical principles involved, how to extend the camera lens to obtain 1:1 magnification and how to use a projector film gate to hold the object film frame. I searched for an acceptable film gate and Michael Mideke gave me a dismantled, primitive 16mm Kodakscope projector – hand cranked, made of sheet metal, lit by incandescent bulb with a perfectly usable gate, claw mechanism, drive sprockets and reel hubs.

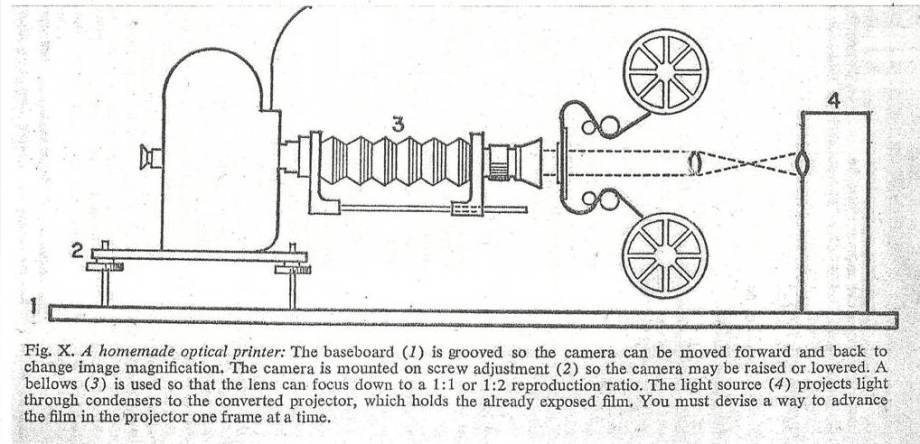

I realized, after running strips of film through the gate, that one could just as well duplicate moving images as a single still. The duplicating camera would have to be single frame advanced while the object film strip was hand cranked forward or back a frame at a time in the projector gate. I built the mounting rig you see in the illustration out of wood, using thumb screws to adjust the camera to align with the frame and added a modern 2000K light for rear illumination. Various coloring and distorting filters were used for effects, later on.

I had a useful background in electronics, optics, engineering and basic carpentry, so was able to design & carry out the mechanical modifications. A still photog gave me the 35mm extension bellows and I found a Cmount adaptor so I could use my 16mm lenses. I later discovered that simple, interchangeable, claw, pull down and gate modifications would permit 8mm film to be enlarged to 16mm, as well.

I had no long-term vision for its use until I started playing with it. The styles & effects were developed out of experimentation under the influence of the 1966 San Francisco cultural milieu.

My first completed experiment was a re-animated composite of some 1950’s B/W television commercials into a culturally critical comedy called “Kosmic Karmic Plot.” By this time the Underground Film scene was erupting, with Bruce Conner’s cut-up films, A Movie and Breakaway, in play around Canyon venues; Bruce Baillie’s visual masterpieces, Mass and Castro Street, as well as Brakhage’s abstractions, my main influences.

I had, simultaneously, become involved with the psychedelic/political theatrics of the SF Diggers, just developing in the Haight Ashbury. And with Ken Kesey, Grateful Dead and some old Oregon high school chums, now Pranksters, in La Honda. By this time the psychedelic revolution was in full swing in The City and cross-pollination was amuck between all the arts, and music filled the air.

Canyon Cinema Coop did its first self-benefit film showing in a store front on Frederick Street, recently acquired by the Diggers as their first Free Store and Free Frame of Reference. [The SF cops showed up to bust the Diggers while Ben Van Meter’s naked wife pranced on-screen in his ”Poon Tang Trilogy,” viewable by all on the street.] I became involved with Haight community movements and neighborhood affairs, vowing to bring the true neighborhood spirit onto the screen. And “Free” into the Canyon vernacular. {For example, the Free Popcorn tradition at Canyon Cinematheque.}

One of the key strategies of Digger culturalism was “Free” - “do your thing and do it for free.” When The First Great Human BeIn happened in Jan 67, numerous filmmakers and television stations turned up to document it, and I shot a little B/W. I proposed a Canyon-wide collective artistic effort to memorialize the event. I got many pieces of footage sent to me with artists’ permission to use but no interest in doing the editing. I acquired a radio station’s audio recording of the stage performances throughout the day.

Left to my own devices with no stake in the original footage, I began to play on the optical printer like a composer might noodle at the piano. I composed a number of sequences and then began to work the sound into a story for the day. (I think I detail more of this creative process in my on-line filmography, so won’t repeat it here.) The photographic inconsistency of some images reflects the various origins of the footage - some previously rephotographed from optical projection by others before it came to me.

Under the influence of the Digger Free idiom I titled it, Be In, A Free Space Film, and initially distributed it through Canyon for free rental. It was widely viewed and I was approached by advertising agencies in LA to do similar effects for their commercials. And by filmmakers to build printers for them, which I declined but was motivated to publish the crude plans in Canyon Cinemanews. With a little help, Bob Nelson used this printer for his own Grateful Dead film & I later did some printing for Gunvor Nelson’s film, My Name Is Oona. I made the second film, Tribal Home Movie #2, later that Spring from the basement of the Grateful Dead’s office house on Ashbury Street.

The SF Art Institute was interested in one of their own and when I demurred they got another technician to build an aerial image printing table for their students. In 1970 Bob Nelson approached me about making a commercially available model for small-time filmmakers. We worked on the concept but ran aground when it came to financing. Another year later (1971) I had the backing of some dope dealers to go ahead on the project and began searching for a camera technician to manufacture the parts. Someone at the Art Institute said I’d better contact Jakko Kurri (sp), a Brooks Camera tech known for converting Bolex Reflex 8mm cameras into Super 8 format.

I met Jakko at his home in San Leandro. In his basement machine shop was the full diagram for his optical printer, the spitting image of my Canyon published diagram, with significant motor drive updates and the dies for the cast parts on the table. I was astounded and offered to partner with him in the process but he had no such inclination. I had taken too long to act myself (ever the ambivalent artist) and lost my opportunity to capitalize it.

Many independent filmmakers bought the JK Optical Printer and years later, in 2007, I encountered three of them still in use at a collective filmmakers’ studio in London.

Loren Sears

November 2017

<< New text box >>